A Word To Occasionally Absent Fathers

“Describe your father in one word.”

One by one, the all-male audience shouted out words like: disconnected; moody; short-tempered; encouraging; quiet; distant; friend; irritable; depressed; non-engaging. While some of the words are positive, most center on a variation of one word: absent. The men were from different backgrounds but all seemed to have this one thing in common: their fathers were absent to some degree or another. This absence may have been physical or emotional, but regardless, it is a common refrain from adult sons about their fathers. While I fully concede that being asked to encapsulate a person in one word is difficult, I find it interesting that the theme of absence continually arises. Why?

"...being asked to encapsulate a person in one word is difficult, [yet] I find it interesting that the theme of absence continually arises."

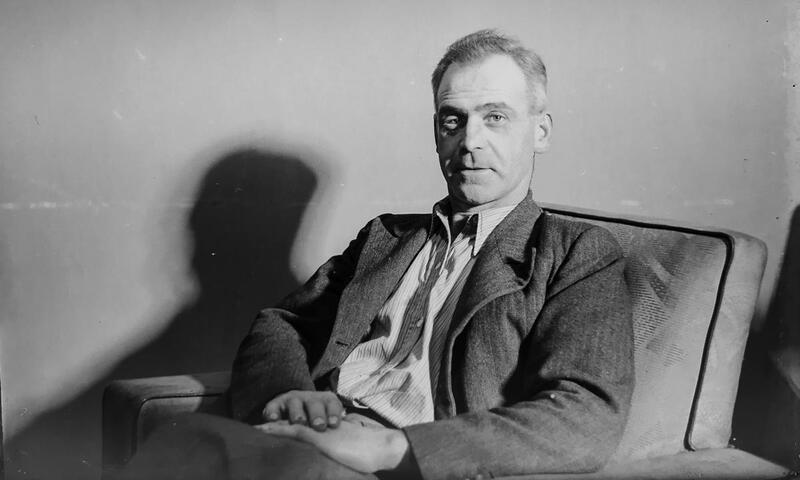

Perhaps the answer lies in a seemingly innocent invention: The T-Model Ford. How can a car contribute to absent fathers? It wasn’t the car per se, but how the car was manufactured. Mass producing these black shoe-box cars starting in 1908 entailed creating massive factories that required men to leave their families and spend long exhausting hours on an assembly line. This period—labeled the Industrial Revolution—fundamentally changed men in two unexpected ways. First, a man’s self-significance shifted from home life to how he performed at work. Since most of his time and energy was spent at work, it’s understandable that how he felt about himself depended more on what his foreman thought than his wife or kids. Second, when a man came home he was physically and emotionally spent. My father worked a back-breaking job at General Motors for over 40 years. When he came home, all he wanted to do was to eat, watch a little television, and sleep—knowing he had to start the day over promptly at 4:30 am. It’s understandable that my dad was often emotionally and physically absent.

Am I any different?

A little self-reflection reveals that I often share the same struggles as my father. When my three boys were young, I was working a full-time job and trying to complete a PhD in communication. As soon as I came home from class or work, I would have a quick meal with the family and then barricade myself in a room to write never-ending research papers. Not only did I want a good grade, but I craved the respect from my professors. Sound familiar? Different venue (grad school), but same result (finding significance outside the family).

As fathers, how can we counter-act this cultural pull to find significance outside the home? I suggest the answer must come in a change of attitude. In his massive best-seller, The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, psychologist Stephen Covey suggests we begin with the end in mind. To do so, Covey has us imagine four people who will speak at our funeral: our spouse, child, boss, and community member. How would you rank them in order of importance? For the thought-exercise to work, you must be brutally honest. No doubt, as a Christian we understand that our spouse and family should come first. But, do they?

"Imagine four people who will speak at our funeral: our spouse, child, boss, and community member. How would you rank them in order of importance?"

In order for change to happen two things must occur.

- We must honestly assess our priorities. “For as he thinks within himself,” assert the ancient writers of Proverbs, “so he is” (23:7). If what our boss thinks about us is more important than what our spouse or children do, then acknowledge it. Change will happen only when we mirror David’s prayer, “Search me, God, and know my heart; test me” (Ps. 139:23).

- We need to prioritize our time and commitments to reflect God’s priorities. As we consult the Bible we learn that as men we are not to abandon the wives of our youth (Mal. 2:14), and we are to embrace our children as a gift from God himself (Ps. 127:3). Jesus often retreated to spend time with His father. He knew that He needed that time often and it isn't a far reach to assume that is a model for the kind of relationship we are to have with our own children.

While I find Covey’s exercise to be helpful, he is missing a key element. As a husband, father, and follower of Jesus, there is one perspective missing from the options given by Covey. At the end of my life, it would be wise for me to not only be concerned with what significant others think about me but most importantly, how my heavenly Father assesses my earthly stewardship of my children—gifts he’s specifically entrusted to me.